Levels, functioning labels, and other ableist hierarchies projected onto the autistic experience

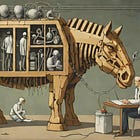

Separating and ranking people hasn't historically worked out well...

There’s a widespread misunderstanding of “the autism spectrum.” For most people, the “spectrum” is interpreted to mean that autism is a degree-based experience ranging from “a little bit” to “a lot.”

But being autistic is binary—you either ARE autistic, or you ARE NOT autistic— as we’ve already explored in a past issue:

The “autism spectrum” actually instead refers to the variety of ways that being autistic can impact people and the many varied expressions of those experiences.

I can understand, in theory, why someone might see value in trying to separate the autistic experience into more discrete categories, given the wide range of autistic experiences. Someone might want to be sure that those varied experiences are being acknowledged and included for research or accommodation purposes, for example.

But most often, the separation and categorization of autistic experiences is used as a way to discount, dismiss or disempower large swaths of the autistic population, so it’s worth reflecting on the usage, implications, and impact of these types of labels, and exploring how we can speak to that diversity without creating separation.

Historical Parsing of The Autistic Experience

“Asperger Syndrome” vs. “Autism Spectrum Disorder”

It’s hard to talk about the early days of autism research and discovery, because it requires acknowledging that it occurred during the Nazi regime, as part of a eugenics program expressly implemented to determine which individuals in society were worthy of life and which weren’t.

It’s horrific and heartbreaking, and it makes me feel sick, but it’s true.

When children had an undesirable level of support needs, had a lower IQ, were nonverbal, and otherwise deviated from the idealized norm, Nazi doctors labeled these children “autistic” (or “childhood schizophrenics”) and sent them to their deaths alongside other persecuted minorities.

“Asperger Syndrome,” so named by Nazi Dr. Hans Asperger, was created as an alternate label for autistic individuals with higher intelligence and lower support needs. These individuals, Asperger argued, could contribute to society and so were worthy of life and spared execution.

In short, Asperger Syndrome was never a separate condition. It’s was just an ableist way to distinguish between the autistics the Nazis believed were worth saving, and those they decided were not. This reality is part of what spurred the dissolving of “Asperger Syndrome” as a separate diagnosis in 2013, when it was re-absorbed into the definition of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Functioning Labels

Functioning Labels were the next iteration of the parsing of the autistic experience. In this new system, autistic individuals who were nonverbal, had learning disabilities, or otherwise needed more day-to-day support were deemed “low-functioning,” while those who were verbal, lacked obvious learning disabilities, and needed less day-to-day support were deemed “high-functioning.”

If you find yourself thinking that “high-functioning” just sounds like a less German way of identifying the “Asperger” autistics that are less inconvenient to those around them, you’d be right.

Since “low-functioning” is such an obviously cruel thing to say to or about someone, and “high-functioning” exists only in contrast to it, you cannot use these labels without implying disgust and disdain for those needing support.

When autistics with few obvious support needs (and their caregivers) use “high-functioning,” they’re creating distance between themselves and those autistics with more obvious support needs: “Oh, no. My child isn’t like THAT. My child has high-functioning autism.”

Similarly—or perhaps, as a result—neurotypicals have come to see “high-functioning” as a bizarre compliment to be paid to autistics with fewer obvious support needs, clarifying that they don’t think of you the way they think of “those” other autistics: “I never would have guessed you’re autistic, though. You’re very high-functioning.”

(Ablist elitism aside, can we also take a moment to recognize the dystopian, capitalist idiocy of quantifying human beings based on how well they “function”?! Because, WTF?? If everyone was rated on a “functionality” scale based on their contribution to the economy, I think we’d have lost these labels a long time ago.)

Levels

In recent years, the inherent ickiness of “functioning labels” has become more obvious, and since the release of the DSM5, the medical establishment has traded in the labels in favor of a “levels” based system, assigning a number between 1 and 3 alongside each ASD diagnosis.

“Level 1” autistics, in this system, are “generally able to function independently with some support,” while Level 3 autistics “require extensive support for daily living and may need assistance with basic tasks.“

Here again, being autistic is defined by how inconvenient it is to those around them, rather than on the autistic person’s own experience. Except this time, by adding numbers to the labels, they’ve approximated a scoring system that inverted the previous low/high labels, essentially rendering “level 1” autistics as “not autistic enough” or not worthy of inclusion in conversations. At the same time, “level 3” can still be used in the same dismissive way that “low-functioning” was used before it.

Why Parsing Always Falls Short

Externalized

The folks creating, assessing, and assigning these categories are not the autistics themselves. (I wrote a post about that here, actually.) As such, these outsiders can only evaluate criteria that they can see or experience as an observer, and rarely (if ever) take into consideration the internal or lived experience of the autistics they are labeling.

Like, imagine if cancer staging was assigned not based on how the cancer cells were impacting the patient’s body but based on how inconvenient it might be to take care of them or how “obvious” it was to those around them that they had cancer?

“Since she still has hair, she must have high-functioning cancer.”

“He vomited after each treatment? Sounds like stage 4.”

EW. First off, it’s cold, impersonal, and dehumanizing, which is reason enough to avoid this type of labeling. But because it’s based almost solely on observable characteristics, it’s also incomplete, insufficient, and potentially inaccurate.

Oversimplified

The reality is that it’s incredibly hard to capture an entire lived experience in a single word or based on a single fact about that person.

The cancer patient in the first example above may well be experiencing terrible pain, horrible side effects of treatment, and struggling to cope emotionally with a difficult prognosis, none of which can be deduced based on a hairstyle. (Not to mention, they could also be masking their hair loss with a hairpiece.) The person in the second example may have responded incredibly well to the aggressive treatment and been deemed cancer-free.

When we describe someone using a functioning label or a level, we’re condensing their entire lived experience in a way that ignores so many of the contributing factors to varied autistic experiences: masking, co-occuring conditions, coping mechanisms, support system, financial situation, access to healthcare, family relationships, age at diagnosis, educational opportunities, intersectional challenges that come with overlapping marginalized identities (like race, age, sexuality), and so much more.

Ableist

We don’t label someone “low-functioning” because they are nearsighted and use corrective lenses to see, so why would we do the same to someone nonverbal who uses an AAC device to communicate?

We don’t use “levels” to distinguish between people who need the support of a knee brace, cane, walker, or wheelchair to get around, so why would we do the same to those who need different kinds of assistance to eat healthy meals, get dressed, or maintain their hygiene?

Regardless of the form the categories take—differing diagnoses, functioning labels, levels, whatever else—they’re largely used to discount, dismiss, or disempower large swaths of the autistic population, creating discord within the autistic community and further marginalizing an already marginalized group.

Specificity Over Separation

I’m not saying there’s no need to differentiate between the varied experiences of autistic people (or of just different people, for that matter).

Without a doubt, our experiences ARE different, and those different experiences need to be accounted for when we’re conducting research, designing accommodations, reviewing policies, and having advocacy conversations to make sure we’re all heard and included.

But I believe there’s a way to speak to those diverse experiences without creating false hierarchies that position members of our already marginalized community as superior or inferior to one another.

We can do this by using language that is:

Accommodation focused

Based on strengths

Contained to their own experience

Determined by their internal experience

Accommodation Focused

Instead of trying to find a category or label for the person or their challenges, focus on specific accommodations or supports that are most helpful or necessary for them. Ask for what is needed instead of focusing on what’s missing.

“dislikes transitions”—> “needs a clear schedule and consistent routine”“easily overstimulated”—> “uses noise-cancelling headphones when working”

For my fellow autistics who tend to default to self-deprecation instead of requesting accommodation, here are some language swaps you can try:

“I’m not good at…”—> “I prefer…”“I can’t…”—> “In order to do that, I need…”“I don’t understand…”—> “Can you clarify…”

Based on Strengths

There’s an instinct to try to describe someone’s autistic experience by emphasizing their deficits—what is difficult or impossible for them to do or understand. When we share an individual’s strengths instead, we’re framing our interaction in terms of what someone is—instead of what they are not— and creating opportunities to connect.

“struggles with spoken instructions”—> “thrives with written instructions” or “loves clear documentation”“hyperfixated on a narrow interest”—> “has an encyclopedic knowledge of ____” or “is an expert in ____” or “would be a great trivia partner.”

Learn more about strength-based approaches here.

Contained to Their Own Experience

Rather than using comparative language that describes autistic individuals in relation to one another (or to neurotypicals), we can use self-contained language that speaks only to their experience, recognizing their individuality and avoiding hierarchical labels.

Instead of:

“She’s speech delayed” [compared to the “average”]

“She’s got a limited vocabulary” [compared to others her age]

“She still isn’t speaking” [compared to the average timeline]

Try:

“She picked up 3 new words since we joined the Mommy & Me play group.”

“She likes to express herself through quotes from her favorite TV shows.”

“Her smile lights up the room when she’s happy, and she’s recently started clapping when she’s excited.”

Determined by Their Internal Experience

Society tends to talk about autistic people’s external behaviors and reactions instead of their internal experiences, but the latter is more respectful of their individuality and humanity.

“freaks out when it’s loud”—> “finds overlapping noises overwhelming”“stims at the dinner table”—> “feels calmer when he has a fidget in hand”

Of course, it may be more difficult for outsiders to understand the internal world of someone who isn’t as expressive or doesn’t have access to AAC devices that would help us understand their communication. Still, we can do our best to avoid defining them by others’ experience of them in the other ways described above.

So what now?

Like most topics I address in

, this is a complicated one. My opinion isn’t the only one, and I don’t ever intend to dismiss or invalidate anyone else’s.But I believe we can accomplish more as a community—in terms of awareness, education, acceptance, advocacy, representation, and more—when we include ALL autistic experiences, rather than forming smaller exclusionary factions created by those outside our community.

All autistic experiences are autistic experiences.

So if we don’t need to separate, don’t.

Really good article. Academic institutions have a long history of preferentially admitting able-bodied students, so unsurprising that this seeps into medical assessments.